The Chartists were a radical political movement of the first half of the 19th century, demanding reform of Parliament, Though they never preached revolutionary violence, they were associated with a number of incidents between 1839 and 1846. They never achieved much; their main importance being that they were the first genuinely working-class political movement in British history; and as such were hailed by Engels.

1842 was a year of economic depression, which led to renewed Chartist agitation, and also to outbreaks of industrial trouble in many areas, which were awarded the good journalistic name of the “Plug Plot” - referring to attempts to force works to close by knocking out the plugs on the steam-boilers. I want to focus here in what happened in North Staffordshire.

On May 21st the Chartist leader Feargus O’Connor visited Stoke. He addressed crowd of 1500, then led a procession through town and held an evening meeting. He attributed distress to financial problems caused by Napoleonic Wars, 30 years earlier, and the only economic nostrum he offered was cultivation of unused land (in which we find the origins of the Allotments movement). One sees how O’Connor gained the reputation of being an ineffective windbag. He said nothing which could be deemed a call to violent revolution, but violence did follow.

There were to be serious disturbances in and around Stoke-on-Trent that summer, involving the colliers and various other trades suffering unemployment or hardship. According to the local paper, the “Stafford Advertiser”, troubles began on July 11th. A miners’ usual pay was 3 shillings and 6 pence for a working day of 10 ½ hours, with an allowance of free coal; but now Sparrow’s works in Longton announced a reduction of wages to 3 shillings [15p] a day, pleading that their prices were being undercut and they could not afford more. The workers refused to accept this and went on strike.

The dispute quickly spread through the coalmines and ironworks of the Potteries, to Silverdale, Kidsgrove and as far as Cheadle. Some firms prudently shut up shop, and others were forced to close by threats of violence to managers and unco-operative workers, and some damage to machinery. There were several mass meetings, addressed by Chartist orators. Staffordshire had as yet no county police force: instead the magistrates had to call out the Yeomanry (a volunteer militia on horseback) and requested the assistance of regular troops. In the meantime, “the most respectable inhabitants” of the Potteries were sworn in as special constables.

During the second half of July things were generally quiet, though Apedale Hall at Chesterton, the home of Richard Heathcote, a coal owner, was besieged for a while. Companies of infantry and dragoons arrived in Stoke, and a few men were convicted of rioting, receiving short prison sentences of two or three months. Most collieries remained closed, with the miners demanding pay of 4 shillings a day, but a few had returned to work. Then, suddenly, the situation boiled over in the second and third weeks of August.

Trouble first broke out in Burslem. Four men had been arrested, but were promptly freed by a mob armed with pickaxes, who then proceeded to smash the windows of the town hall. The George Inn was then trashed and plundered, followed by the home of Mr Riles, the superintendent of police, and other houses. By the time the soldiers arrived the rioters had dispersed.

The peak of the violence came in Hanley on Monday, August 15th. A mob said to number several thousand first freed their comrades from the town lockup, then ransacked the police station, scattering its papers. They then moved on to the Court of Requests at Shelton Bridge, where books and documents were seized and thrown into the canal. Attacks then followed all over the Potteries. The windows of Stoke police station were smashed, and the homes of Mr Allin at Fenton and Mr Rose, a magistrate, at Penkhull were looted. At Longton the town hall and police station were attacked, and the Reverend Dr Vale, Rector of Longton, had his house ransacked and his furniture and books carried out and burnt on a bonfire. Many women came on the scene and were reported to have drunk themselves insensible on Dr Vale’s looted wine. Albion House in Old Hall Street, Shelton (which is now part of Hanley), the home of the magistrate Mr William Parker, was plundered and then set on fire, as was that of the Reverend Mr Aitkins, vicar of Hanley, who saw his extensive library destroyed.

No apparent effort was made by the authorities to put out these fires, and it seems that the troops were always a couple of steps behind the rioters. The dragoons were, however, ready the next day, the 16th, when a Chartist meeting was held in Hanley, and a mob from Leek was reported to be marching in through Smallthorne. The Riot Act was read, stones were thrown at the troops and shots were fired; one man was killed and a number wounded. An inquest was heard the next day, in the course of which the coroner, Mr Harding, learnt that his house had been set on fire!

Then, for no clear reason, the violence subsided as quickly as it had begun. There remained merely the tidying-up. Damage was estimated at over £10,000, including £4,000 at Mr Parker’s house, £2,000 at the Reverend Mr Aitkins’s vicarage and £1500 at Dr Vale’s. A special commission was set up to try rioters. These included Joseph Capper, a blacksmith from Tunstall, who was charged with sedition resulting from a meeting back in June, and William Ellis, a potter from Burslem and a Chartist lecturer, who was charged with treason. Altogether 54 men were sentenced to transportation (11 of them for life), 153 imprisoned, and 66 acquitted or discharged. The solitary dead man, who had been shot through the head by the troops at Burslem on the 16th, proved to be Josiah Henry, a shoemaker from Leek, aged just 19 but already a widower and a father of three.

These disturbances were in fact typical of riots which had been taking place in England since the mid- 18th century; and by this time seem curiously anachronistic. The causes were always economic, resulting from trade slumps which led to pressure on wages and on living standards, but only irrelevant political solutions were offered. The rioters never killed anyone in these occasions, and here in Stoke the only fatal casualty was the man shot by the troops - unless we include Thomas Adkins, a sawyer from Lane End, who died of alcoholic poisoning after drinking too much stolen liquor. On the other hand the rioters, as always, caused a great deal of damage to property, targeting their attacks on symbols of authority and the homes of unpopular people. No one, least of all the Chartist leaders, had any kind of revolutionary strategy. The demands of the rioters, as in the previous century, were essentially conservative, centring on restoring old rates of pay and prices. No-one as yet had any concept of “workers’ control”.

Nor had methods of riot control changed much over the decades. True, soldiers could now reach a town by train in a few hours, but once they were there, communications and troop movements could proceed no faster than a man on horseback - or, more likely in a conurbation like Stoke, no faster than a man on foot. Furthermore, soldiers with only slow-loading single-shot weapons had little advantage over a rampaging mob. Over the next half century, everything would change: government would become much more powerful and society would become much more peaceful, but also theories of revolution would be developed, and the huge pointless destructive 18th century style riots would become a thing of the past. (In any case, British riots were sedate affairs compared with contemporary disturbances in New York, where Negroes were tortured and murdered, and unpopular men had their eyes gouged out. Full gruesome details can be found in Herbert Asbury's "Gangs of New York", from which the film of the same title was, rather loosely, derived)

It is astonishing to learn that, even after this experience, there was still opposition amongst the ruling classes to Staffordshire having its own county police force. The creation of one was being discussed in Parliament at this very time, but in October Lord Sandon voted in the House of Lords that such a force should function only in the urban areas, not in the rural districts. As late as this, the great landowners still resented any loss of their local power.

The 1842 riots are the scene for Benjamin Disraeli’s novel “Sybil; or the Two Nations”, published in 1845 (the “two nations” being, as Disraeli explains, “THE RICH AND THE POOR”, putting these words in block capitals to make sure that the reader gets the message. The novel focuses on the Black Country around Birmingham rather than the Potteries, and climaxes with the sacking and burning of the stately home of the unpopular nobleman, Lord de Mowbray, by a mob of coalminers and metalworkers from Willenhall (which Disraeli calls “Wodgate”). Perhaps unexpectedly for a future Conservative Prime Minister, Disraeli sympathises with his working-class characters, and his Chartist leaders are portrayed as heroic figures. (See my separate entry on Disraeli’s novel)

.

(My thanks to the staff of the William Salt Library, Stafford, for their help in researching this piece)

Monday 24 June 2013

Wednesday 12 June 2013

The Romance of the Ashes

On a miserably cold and wet day at the Oval cricket ground in August 1882, the England team, set a mere 85 runs to beat the Australians, were skittled out by Frederick Spofforth, the original “demon bowler”, and lost the match. In this debacle the great W. G. Grace scored 32, but the other ten Englishmen managed just 41 between them. A few days later, the following mock obituary notice appeared in the “Sporting Times”:-

“In affectionate memory of English Cricket, which died at the Oval on 29th August 1882, deeply lamented by a large circle of friends and acquaintances. R.I.P. (N.B. The body will be cremated and the ashes taken to Australia)"

(Like all good humorists, the author managed to combine two separate issues currently in the news; cremation of the dead being a controversial matter of doubtful legality, bitterly opposed by many in the Church)

Thus began the most famous tradition in cricket: the contest between England and Australia for the “Ashes”. The 1882 match was not the first between the two countries, but it stirred the popular imagination as never before. But the “Ashes” did not yet actually exist. This is the romantic story of how they began.

The victorious Australians were still playing in England when an English team set sail for Australia on September 14th. It consisted of just twelve players; an absurdly small squad by today’s standards, which was reduced even further when their fast bowler, Fred Morley, broke a rib in an accident. Only three men from the Oval match were included; the most notable absentee being W. G. Grace. The captain was a tall, handsome young aristocrat: the Honourable Ivo Bligh, second son of the Earl of Darnley.

This is Bligh's team. Standing: Barnes, Morley, C.T.Studd, Vernon, Leslie. Seated: G.B.Studd, Tylecote, Bligh, Steel, Read. In front: Barlow, Bates. Of these, Barnes, Barlow, Bates and Morley were professional cricketers from working-class backgrounds; the rest were gentleman amateurs from the great public (independent) schools and universities. In no other sport at that time would amateurs and professionals have played together for their country.

Bligh was an odd choice in many ways. He was just 23 years old, and had never played international cricket (the term “Test Matches” did not come into use until many years later). At Eton and Cambridge University he had excelled at tennis and racquets as well as cricket, and had scored over a thousand runs for Kent in the 1880 season; but he would never have been rated as one of the best batsmen in England, and although clearly a fine athlete, his health was never good. Nor would he make any significant contribution with the bat on this tour: his attainment of immortality came from a different source.

On the voyage out, which lasted two months, the team made the acquaintance of Sir William and Lady Janet Clarke. Sir William, a great philanthropist and past president of the Melbourne Cricket Club, was said to be the richest man in Australia. He invited them to spend Christmas at Rupertswood, his very grand country house outside Melbourne. This was to be a momentous event both in the life of Ivo Bligh and in the history of cricket, because the Clarke household included a young lady who acted as the children’s governess and music teacher as well as a friend of Lady Janet. She was Miss Florence Morphy, aged 22, an orphan; the seventh and youngest child of a police magistrate of Irish extraction. Bligh was immediately smitten with her.

Meanwhile there were matches to be played. It was an unusually wet summer in Australia, with results being affected by rain on uncovered pitches; but large crowds attended, often running to 20,000 or more per day. The first match against William Murdoch’s Australian team took place at Melbourne at the end of December, and resulted in England losing by 9 wickets after succumbing to the off-spin of George Palmer and being forced to follow on. The second match, also at Melbourne, began on January 19th, and this time there was a comprehensive victory for England, by an innings and 27 runs. William Bates took 14 wickets in the match, including a hat-trick. It would be all to play for in the third match at Sydney a week later.

In his capacity as captain, Bligh was often called upon to make speeches. He generally spoke of his goal being “to beard the kangaroo in its den” and “to bring back the ashes”. He was of course referring to something which did not actually exist, and must initially have puzzled his audiences, but Murdoch’s Australian team understood the reference to the “Sporting Times” joke, and were able to reply in kind. Very soon, Australian papers were taking up the theme: who could claim possession of the ashes?

The Sydney match ran into four days. After the first innings it was evenly balanced, with England holding a lead of just 29 runs. On the third day a huge crowd turned up to watch Spofforth bowl out England. 7 for 44 to the dreaded demon bowler; England dismissed for a paltry 123: the match and the ashes were surely Australia’s. But no! Richard Barlow, bowling slow-medium left-arm, did even better than Spofforth: 7 for 40; Australia collapsing to 83 all out, with only two men reaching double figures: an easy win for England! Unlike the popular image of Victorian cricket, the match was an ill-tempered affair, with each side accusing the other of deliberately cutting up the pitch to aid the bowling of Spofforth and Barlow, and some of the players reportedly almost coming to blows at one point.

There followed a fourth match in mid-February against a “Combined XI”, when not even a century by Allan Steel (the only one of the series) could prevent an Australian victory. It has been disputed ever since whether this constituted a “proper test match”; but at the time no-one appeared to question that England had won the right to “take back the ashes”. Bligh had contributed very little as a player (his highest score was only 19, and he did not bowl); the victories resulting from the bowling of the northern professionals; Bates of Yorkshire and Barlow of Lancashire. But as captain, Bligh was given the publicity and much of the credit.

He had other matters on his mind. On January 3rd he wrote to his parents requesting permission to marry Florence Morphy. Lady Janet Clarke had already warned him that Lord and Lady Darnley would not be happy about a son of theirs attaching himself to a penniless girl of no family; and she was of course quite right: parental consent was not given. This whole episode puts us firmly back into the Victorian period. Here we have a highly educated man, on the verge of his 24th birthday, in the process of achieving great international sporting fame and success, yet feeling he could not become engaged to be married without the approval of his parents - and the approval being denied, apparently for reasons of pure snobbery! Bligh pondered his next step.

But what of the Ashes themselves? Here, unfortunately, the evidence is confused and contradictory. At some stage, presumably at Rupertswood, Bligh was presented with a tiny urn; such as might have stood on a lady’s dressing table holding perfume; but now containing ashes. Ashes of what? It is usually believed to be the ashes from burning a bail, or a stump; but it is sometimes said to be the ashes of the leather casing of a cricket ball. And when exactly was it presented? After the third match the Melbourne magazine “Punch” published some execrable verses about the return of the “urn” to England. Does this mean that the urn had already been presented, and furthermore that this was common knowledge? Or was the magazine speaking purely metaphorically? Maybe more than one urn was presented? These puzzles are unlikely ever to be solved. Quite separately, a Queensland lady in February gave Bligh a small velvet bag to hold the urn. He sailed back to England in May 1883, taking the urn with him. It would stand on his mantelpiece for the rest of his life. What ranked highest in his mind, however, was winning his parents’ consent to his marriage.

He went about the task with great determination, as befitted an international sporting captain. He told his father that, rather than give up Florence, he would settle permanently in Australia. After six weeks, Lord Darnley gave up the struggle, and wrote to Florence agreeing to the match, though with no great enthusiasm.

Ivo Bligh returned to Australia to marry Florence Morphy in February 1884. The bride was given away by Sir William Clarke, and the wedding breakfast was held at Rupertswood. None of Bligh's family attended. The Melbourne “Punch” celebrated the event in yet more extremely bad poetry. After a honeymoon in New Zealand the happy couple returned to England.

Ill health meant that Bligh played little cricket after this, and he never represented England again. Indeed, for the rest of his life he comes across as a curiously diffident personality. It was almost as if he had exhausted his entire life’s supply of energy and initiative in winning the Ashes and gaining his father’s consent to his marriage. (Alternatively, like many sportsmen since, he simply did not know what to do with himself after retiring) He tried working as a stockbroker, but soon gave up. He moved to Melbourne for a couple of years, but that didn’t work out either. It was Florence who emerged as the stronger personality, and she must have found these years frustrating. They had three children, but money was short and there was little prospect of improvement.

Lord Darnley died in 1896, and Ivo Bligh’s elder brother, Edward, succeeded to the title. He was a highly eccentric personality, and had not managed to father a male heir when he died suddenly in 1900. So, unexpectedly, Ivo and Florence found themselves the 8th Earl and Countess of Darnley and owners of the family home of Cobham Hall in Kent. In many ways this was less good than it sounded. The great house was very expensive to run, a combination of death duties and collapsing agricultural prices meant that the estate was heavily encumbered with debt, and any wealth had to be shared with brother Edward’s widow.

As a nobleman, Bligh had a part to play in the nation. The Darnley title was an Irish one, so he sat in the House of Lords as an Irish representative peer, and occasionally spoke in debates. He also served as a Deputy Lord-Lieutenant and a Justice of the Peace, but he still appeared a shy, diffident character. Florence, by contrast, relished her new status as a great lady. She became a close friend of Queen Mary, and she received the Australian Prime Minister, Billy Hughes, when he came to England. In the First World War she opened Cobham Hall as a nursing home for wounded Australian servicemen, with herself acting as Matron, and was created a Dame of the British Empire (D.B.E.) for her war work. She had indeed come a very long way from her former life as an orphan music teacher in Melbourne!

Financial worries continued, however. Much of the Darnley estates had to be sold, and in 1925 the family’s magnificent collection of paintings was auctioned off. This raised over £70,000, but since it included works by Titian, Poussin, Lely, Canaletto, Gainsborough and others, one can only guess at how many millions such a sale would fetch today! In 1923 Cobham Hall was rented out to an American, and the family moved to a smaller house in the grounds. Such a decline was not atypical of the old aristocracy at that time. (Cobham Hall is now a girls' school)

Ivo Bligh, 8th Earl of Darnley, died in 1927, aged only 68. The little urn with the Ashes was presented to the M.C.C., and it has remained at Lord’s ever since. Florence, now Dowager Countess of Darnley, managed to further confuse the story of the Ashes when she told Bill Woodfull, the captain of the 1930 Australian team in England, that Lady Janet Clarke had burnt a stump and presented it to Bligh in a little wooden urn - whereas the existing urn is made of terra-cotta. One imagines her as a formidable matriarch in her later years: her daughter once referred to her as "the old dragon"!

She died in 1944: the last direct link with the story of the Ashes.

The words pasted on the little urn are taken from the inimitable verse of the Melbourne "Punch":-

"When Ivo goes back with the urn, the urn;

Studds, Steel, Read and Tylecote return, return;

The welkin will ring loud,

The great crowd will feel proud,

Seeing Barlow and Bates with the urn, the urn;

And the rest coming home with the urn".

(Sources: "Wisden Book of Test Cricket, 1876-77 to 1977-78": "Wisden Book of Cricketers' Lives": Illingworth and Gregory, "The Ashes": Berry and Peploe, "Cricket's Burning Passion")

“In affectionate memory of English Cricket, which died at the Oval on 29th August 1882, deeply lamented by a large circle of friends and acquaintances. R.I.P. (N.B. The body will be cremated and the ashes taken to Australia)"

(Like all good humorists, the author managed to combine two separate issues currently in the news; cremation of the dead being a controversial matter of doubtful legality, bitterly opposed by many in the Church)

Thus began the most famous tradition in cricket: the contest between England and Australia for the “Ashes”. The 1882 match was not the first between the two countries, but it stirred the popular imagination as never before. But the “Ashes” did not yet actually exist. This is the romantic story of how they began.

The victorious Australians were still playing in England when an English team set sail for Australia on September 14th. It consisted of just twelve players; an absurdly small squad by today’s standards, which was reduced even further when their fast bowler, Fred Morley, broke a rib in an accident. Only three men from the Oval match were included; the most notable absentee being W. G. Grace. The captain was a tall, handsome young aristocrat: the Honourable Ivo Bligh, second son of the Earl of Darnley.

This is Bligh's team. Standing: Barnes, Morley, C.T.Studd, Vernon, Leslie. Seated: G.B.Studd, Tylecote, Bligh, Steel, Read. In front: Barlow, Bates. Of these, Barnes, Barlow, Bates and Morley were professional cricketers from working-class backgrounds; the rest were gentleman amateurs from the great public (independent) schools and universities. In no other sport at that time would amateurs and professionals have played together for their country.

Bligh was an odd choice in many ways. He was just 23 years old, and had never played international cricket (the term “Test Matches” did not come into use until many years later). At Eton and Cambridge University he had excelled at tennis and racquets as well as cricket, and had scored over a thousand runs for Kent in the 1880 season; but he would never have been rated as one of the best batsmen in England, and although clearly a fine athlete, his health was never good. Nor would he make any significant contribution with the bat on this tour: his attainment of immortality came from a different source.

On the voyage out, which lasted two months, the team made the acquaintance of Sir William and Lady Janet Clarke. Sir William, a great philanthropist and past president of the Melbourne Cricket Club, was said to be the richest man in Australia. He invited them to spend Christmas at Rupertswood, his very grand country house outside Melbourne. This was to be a momentous event both in the life of Ivo Bligh and in the history of cricket, because the Clarke household included a young lady who acted as the children’s governess and music teacher as well as a friend of Lady Janet. She was Miss Florence Morphy, aged 22, an orphan; the seventh and youngest child of a police magistrate of Irish extraction. Bligh was immediately smitten with her.

In his capacity as captain, Bligh was often called upon to make speeches. He generally spoke of his goal being “to beard the kangaroo in its den” and “to bring back the ashes”. He was of course referring to something which did not actually exist, and must initially have puzzled his audiences, but Murdoch’s Australian team understood the reference to the “Sporting Times” joke, and were able to reply in kind. Very soon, Australian papers were taking up the theme: who could claim possession of the ashes?

The Sydney match ran into four days. After the first innings it was evenly balanced, with England holding a lead of just 29 runs. On the third day a huge crowd turned up to watch Spofforth bowl out England. 7 for 44 to the dreaded demon bowler; England dismissed for a paltry 123: the match and the ashes were surely Australia’s. But no! Richard Barlow, bowling slow-medium left-arm, did even better than Spofforth: 7 for 40; Australia collapsing to 83 all out, with only two men reaching double figures: an easy win for England! Unlike the popular image of Victorian cricket, the match was an ill-tempered affair, with each side accusing the other of deliberately cutting up the pitch to aid the bowling of Spofforth and Barlow, and some of the players reportedly almost coming to blows at one point.

There followed a fourth match in mid-February against a “Combined XI”, when not even a century by Allan Steel (the only one of the series) could prevent an Australian victory. It has been disputed ever since whether this constituted a “proper test match”; but at the time no-one appeared to question that England had won the right to “take back the ashes”. Bligh had contributed very little as a player (his highest score was only 19, and he did not bowl); the victories resulting from the bowling of the northern professionals; Bates of Yorkshire and Barlow of Lancashire. But as captain, Bligh was given the publicity and much of the credit.

He had other matters on his mind. On January 3rd he wrote to his parents requesting permission to marry Florence Morphy. Lady Janet Clarke had already warned him that Lord and Lady Darnley would not be happy about a son of theirs attaching himself to a penniless girl of no family; and she was of course quite right: parental consent was not given. This whole episode puts us firmly back into the Victorian period. Here we have a highly educated man, on the verge of his 24th birthday, in the process of achieving great international sporting fame and success, yet feeling he could not become engaged to be married without the approval of his parents - and the approval being denied, apparently for reasons of pure snobbery! Bligh pondered his next step.

But what of the Ashes themselves? Here, unfortunately, the evidence is confused and contradictory. At some stage, presumably at Rupertswood, Bligh was presented with a tiny urn; such as might have stood on a lady’s dressing table holding perfume; but now containing ashes. Ashes of what? It is usually believed to be the ashes from burning a bail, or a stump; but it is sometimes said to be the ashes of the leather casing of a cricket ball. And when exactly was it presented? After the third match the Melbourne magazine “Punch” published some execrable verses about the return of the “urn” to England. Does this mean that the urn had already been presented, and furthermore that this was common knowledge? Or was the magazine speaking purely metaphorically? Maybe more than one urn was presented? These puzzles are unlikely ever to be solved. Quite separately, a Queensland lady in February gave Bligh a small velvet bag to hold the urn. He sailed back to England in May 1883, taking the urn with him. It would stand on his mantelpiece for the rest of his life. What ranked highest in his mind, however, was winning his parents’ consent to his marriage.

He went about the task with great determination, as befitted an international sporting captain. He told his father that, rather than give up Florence, he would settle permanently in Australia. After six weeks, Lord Darnley gave up the struggle, and wrote to Florence agreeing to the match, though with no great enthusiasm.

Ivo Bligh returned to Australia to marry Florence Morphy in February 1884. The bride was given away by Sir William Clarke, and the wedding breakfast was held at Rupertswood. None of Bligh's family attended. The Melbourne “Punch” celebrated the event in yet more extremely bad poetry. After a honeymoon in New Zealand the happy couple returned to England.

Ill health meant that Bligh played little cricket after this, and he never represented England again. Indeed, for the rest of his life he comes across as a curiously diffident personality. It was almost as if he had exhausted his entire life’s supply of energy and initiative in winning the Ashes and gaining his father’s consent to his marriage. (Alternatively, like many sportsmen since, he simply did not know what to do with himself after retiring) He tried working as a stockbroker, but soon gave up. He moved to Melbourne for a couple of years, but that didn’t work out either. It was Florence who emerged as the stronger personality, and she must have found these years frustrating. They had three children, but money was short and there was little prospect of improvement.

Lord Darnley died in 1896, and Ivo Bligh’s elder brother, Edward, succeeded to the title. He was a highly eccentric personality, and had not managed to father a male heir when he died suddenly in 1900. So, unexpectedly, Ivo and Florence found themselves the 8th Earl and Countess of Darnley and owners of the family home of Cobham Hall in Kent. In many ways this was less good than it sounded. The great house was very expensive to run, a combination of death duties and collapsing agricultural prices meant that the estate was heavily encumbered with debt, and any wealth had to be shared with brother Edward’s widow.

As a nobleman, Bligh had a part to play in the nation. The Darnley title was an Irish one, so he sat in the House of Lords as an Irish representative peer, and occasionally spoke in debates. He also served as a Deputy Lord-Lieutenant and a Justice of the Peace, but he still appeared a shy, diffident character. Florence, by contrast, relished her new status as a great lady. She became a close friend of Queen Mary, and she received the Australian Prime Minister, Billy Hughes, when he came to England. In the First World War she opened Cobham Hall as a nursing home for wounded Australian servicemen, with herself acting as Matron, and was created a Dame of the British Empire (D.B.E.) for her war work. She had indeed come a very long way from her former life as an orphan music teacher in Melbourne!

Financial worries continued, however. Much of the Darnley estates had to be sold, and in 1925 the family’s magnificent collection of paintings was auctioned off. This raised over £70,000, but since it included works by Titian, Poussin, Lely, Canaletto, Gainsborough and others, one can only guess at how many millions such a sale would fetch today! In 1923 Cobham Hall was rented out to an American, and the family moved to a smaller house in the grounds. Such a decline was not atypical of the old aristocracy at that time. (Cobham Hall is now a girls' school)

Ivo Bligh, 8th Earl of Darnley, died in 1927, aged only 68. The little urn with the Ashes was presented to the M.C.C., and it has remained at Lord’s ever since. Florence, now Dowager Countess of Darnley, managed to further confuse the story of the Ashes when she told Bill Woodfull, the captain of the 1930 Australian team in England, that Lady Janet Clarke had burnt a stump and presented it to Bligh in a little wooden urn - whereas the existing urn is made of terra-cotta. One imagines her as a formidable matriarch in her later years: her daughter once referred to her as "the old dragon"!

She died in 1944: the last direct link with the story of the Ashes.

The words pasted on the little urn are taken from the inimitable verse of the Melbourne "Punch":-

"When Ivo goes back with the urn, the urn;

Studds, Steel, Read and Tylecote return, return;

The welkin will ring loud,

The great crowd will feel proud,

Seeing Barlow and Bates with the urn, the urn;

And the rest coming home with the urn".

(Sources: "Wisden Book of Test Cricket, 1876-77 to 1977-78": "Wisden Book of Cricketers' Lives": Illingworth and Gregory, "The Ashes": Berry and Peploe, "Cricket's Burning Passion")

Thursday 6 June 2013

A Lost Family

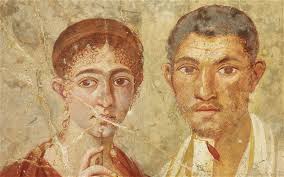

Judging by the family portraits they left us, they must have been well-off. The husband and wife are depicted side-by-side, wearing their best clothes. He chose to be painted holding an official-looking document with a red seal attached, suggesting something legal. His wife, more informally, is shown sucking the end of a pencil, with a quizzical expression on her face, as if she was wondering whether she might have left something off her shopping list. In a separate picture a younger woman, presumably their daughter, is also sucking a pencil and clutching a notebook in her left hand, but her expression more resembles a poet searching for the next line.

They would have been proud of their home, with its brightly-painted walls. They had a dog, and like many home-owners since, they had put up a sign warning intruders that their dog was very fierce. They would especially have loved their neat little garden, which had a few statues amongst the flowers, and we can imagine them enjoying a drink of wine there with their friends in a summer evening. Their surviving pictures show they had good taste, and maybe they regarded the somewhat explicit artworks favoured by their neighbours as a bit vulgar. Our family preferred pictures of birds and plants. One particularly delightful painting shows a young girl gathering spring flowers, so realistic that you can see the blossom falling around her.

But it was not blossom which fell on our family on that terrible day many years ago: it was something far more deadly. And they are gone, so we are no longer certain even of their names, but their home and their pictures still survive; pictures in which the blossom never did fall, but is frozen forever in an eternal spring.

They would have been proud of their home, with its brightly-painted walls. They had a dog, and like many home-owners since, they had put up a sign warning intruders that their dog was very fierce. They would especially have loved their neat little garden, which had a few statues amongst the flowers, and we can imagine them enjoying a drink of wine there with their friends in a summer evening. Their surviving pictures show they had good taste, and maybe they regarded the somewhat explicit artworks favoured by their neighbours as a bit vulgar. Our family preferred pictures of birds and plants. One particularly delightful painting shows a young girl gathering spring flowers, so realistic that you can see the blossom falling around her.

But it was not blossom which fell on our family on that terrible day many years ago: it was something far more deadly. And they are gone, so we are no longer certain even of their names, but their home and their pictures still survive; pictures in which the blossom never did fall, but is frozen forever in an eternal spring.

(This was written after visiting the Pompeii exhibition at the British Museum. I have, of course, combined details from several different houses in the town; but that is how they were set out in the exhibition)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)